I first heard this brief negotiation story from my friend and colleague, William Ury, though it turns out to have variants in many cultures. The lessons of this tale have been invaluable to me in advising on truly challenging business and political negotiations. I’ll sketch two such cases after the story (one from Blackstone’s early fundraising days, the other from an impasse between Egypt and Israel).

The Story

A beloved man passes away in a small Middle Eastern village. After the funeral, his three sons somberly return home to open his will. By far the most valuable part of his estate consists of 17 prize goats, which represent the main store of value in that local region. With trepidation, the sons open the document: the oldest son is entitled to half of the father’s wealth, the middle son is granted a third, and the youngest son gets one-ninth.

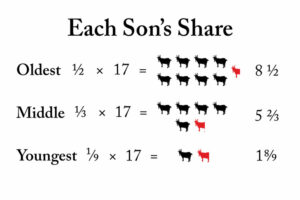

Starting to divide the estate, the oldest claims his half of the 17 goats, which inconveniently, was eight-and-a-half (8.5). Not wanting to cut one of the valuable animals in half, he demanded nine of the goats, but his brothers emphatically said “no way, you’re only entitled to half.” Moving on from that unresolved issue, the middle son claims his third of the 17, which equals five and two-thirds (5.67). When he demands six goats, his brothers indignantly refuse.

Tempers rising, they move to the youngest son. His allotted one-ninth of 17 equates to one and eight-ninths (1.89) of a goat. He mutters that he should clearly get “at least two” given how close his share is to that number. After “no” from his brothers —”that’s all you’re due” they maintain—he grouses that maybe he should just cut off the tail or nose of a goat so he’d get his exact share. No go.

Following fruitless debate and increasing anger—deeply inappropriate at such a somber time—they turn in desperation to an elderly woman in the village who has a reputation for wisely sorting out conflicts. She tries this and that option, all to no avail. There just aren’t enough goats to go around. But then she hits on a solution and describes it to the three sons.

Soberly, she says “your father was a great man, revered by all in this village. In his honor and to ensure peace in his house, I want you to take my prize goat, the only other one in the village of this priceless species. Then, with 18 goats, your estate division problem will be easy.”

And it surely was: the eldest son takes half of eighteen, which is nine; the middle son takes his third of 18, which is six; and the youngest takes his one-ninth of 18, which is two.

Gratified, they count up their shares: nine for the oldest, six for the middle son, and two for the youngest. But 9 + 6 + 2=17! Astonished, the three each claim the full amount due according to the will, but there is one left over. So they give the 18th goat back to the wise woman and they are done! They hadn’t needed that 18th goat after all.

Whoa! What gives? The three sons had foundered on an old negotiation trap: they had immediately jumped to the conflict-inducing conclusion that there simply weren’t enough goats to go around. Insufficient resources! Versions of this common mental leap often lead to bitter battles over budgets, prices, or headcounts: “there’s just not enough to go around, so we’ll have to fight about it.” In fact, this mental jump is so common that psychologists have studied it and given it a name: “the mythical fixed pie.”

But looking at the conflict through another lens, or reframing it, one quickly realizes that there were enough goats to go around. This wasn’t a problem of insufficiency; rather, it was a problem of indivisibility: 17 can’t evenly be divided in half, thirds, or ninths—but 18 can be. (For the wonky: supply the 18th goat and the new total number, 18, is divisible by 2, 3, or 9—with one goat left over to give back. Fortunately, the father’s will only allocated 17/18ths of his estate; hence the elegant solution. For the really wonky: try this story with the same will and 35 goats; then the wise woman gets two goats back for her one—and each son gets his full share!.)

The Lessons

More broadly and directly applicable to many of today’s negotiations and conflicts, this story prompts us to look behind incompatible bargaining positions to see whether underlying interests can be reconciled. Doing so, often uncovers mutually beneficial solutions. Consider two quick examples, one from business, the other international relations.

Early in my career, when I was working at the Blackstone Group during its startup years, the firm was trying desperately to raise its first fund. Although its co-founders, Pete Peterson and Steve Schwarzman, had glittering records as deal advisors, especially on mergers and acquisitions (M&A), investors were reluctant to give their money to a firm like Blackstone without buyout experience. After months of fruitless efforts, negotiations with Prudential Insurance finally succeeded, but with tough conditions for its vital $100 million investment—a high rate of return to Prudential before Blackstone received any profits, a share of Blackstone’s advisory fees, etc. Contemplating an upcoming fundraising trip to Japan, Pete and Steve at best expected a similar kind of negotiation with Nikko Securities: how large a capital investment could they get from the Japanese firm while seeking to give up as little as possible in terms? Still, off they flew.

Early in my career, when I was working at the Blackstone Group during its startup years, the firm was trying desperately to raise its first fund. Although its co-founders, Pete Peterson and Steve Schwarzman, had glittering records as deal advisors, especially on mergers and acquisitions (M&A), investors were reluctant to give their money to a firm like Blackstone without buyout experience. After months of fruitless efforts, negotiations with Prudential Insurance finally succeeded, but with tough conditions for its vital $100 million investment—a high rate of return to Prudential before Blackstone received any profits, a share of Blackstone’s advisory fees, etc. Contemplating an upcoming fundraising trip to Japan, Pete and Steve at best expected a similar kind of negotiation with Nikko Securities: how large a capital investment could they get from the Japanese firm while seeking to give up as little as possible in terms? Still, off they flew.

Listening to Nikko with open minds and probing more broadly, they learned that the Japanese giant badly wanted to enter the American M&A market. Knowing from experience that Nikko had no chance of success on its own, Steve later recounted the moment a solution struck him. Reframing the challenge away from a battle over investment amounts and terms, he thought “Why not form a joint venture? [Nikko] could bring Japanese companies to America, and Blackstone could work with them. A fifty-fifty split of revenues on condition they also invested in our first fund. It was a creative way for both of us to get what we wanted. We needed money for our fund; they needed to build their M&A business.” Given Nikko’s close ties to the Mitsubishi group, which also invested, Pete and Steve traveled back to New York with $325 million. Together with the investments of Prudential and a few others, the Japanese money ensured the success of Blackstone’s first fund.

Listening to Nikko with open minds and probing more broadly, they learned that the Japanese giant badly wanted to enter the American M&A market. Knowing from experience that Nikko had no chance of success on its own, Steve later recounted the moment a solution struck him. Reframing the challenge away from a battle over investment amounts and terms, he thought “Why not form a joint venture? [Nikko] could bring Japanese companies to America, and Blackstone could work with them. A fifty-fifty split of revenues on condition they also invested in our first fund. It was a creative way for both of us to get what we wanted. We needed money for our fund; they needed to build their M&A business.” Given Nikko’s close ties to the Mitsubishi group, which also invested, Pete and Steve traveled back to New York with $325 million. Together with the investments of Prudential and a few others, the Japanese money ensured the success of Blackstone’s first fund.

Beyond corporate success stories, this kind of reframing and probing interests has wide application, including to issues of war and peace. When I was recently writing a book about Henry Kissinger as a negotiator, a conversation with the former Secretary of State reminded me of such an example. After the 1973 war, when he was mediating the dispute between Egypt and Israel over the Sinai, their positions on where to draw the boundary were wholly incompatible and no proposed map was acceptable. They were deadlocked, literally, on “where to draw the line in the sand.” Yet, with Kissinger’s prompting, they probed behind their opposing positions, reframing the conflict away from how much territory one would get and the other had to give. In so doing, they uncovered a vital difference between their underlying interests and priorities: the Israelis fundamentally cared more about security, while the Egyptians, having had the Sinai under various colonial powers over the years, cared more about sovereignty. The interim solution: a demilitarized zone under the Egyptian flag. Each got what it cared about most at relatively low cost to the other.

Beyond corporate success stories, this kind of reframing and probing interests has wide application, including to issues of war and peace. When I was recently writing a book about Henry Kissinger as a negotiator, a conversation with the former Secretary of State reminded me of such an example. After the 1973 war, when he was mediating the dispute between Egypt and Israel over the Sinai, their positions on where to draw the boundary were wholly incompatible and no proposed map was acceptable. They were deadlocked, literally, on “where to draw the line in the sand.” Yet, with Kissinger’s prompting, they probed behind their opposing positions, reframing the conflict away from how much territory one would get and the other had to give. In so doing, they uncovered a vital difference between their underlying interests and priorities: the Israelis fundamentally cared more about security, while the Egyptians, having had the Sinai under various colonial powers over the years, cared more about sovereignty. The interim solution: a demilitarized zone under the Egyptian flag. Each got what it cared about most at relatively low cost to the other.

Facing complete impasses in business, financial, and diplomatic negotiations in which I’ve been involved, I’ve often sought a high value-low cost solution. Can I imagine an 18th goat for that situation? More often than one might expect, I’m happily surprised with what turns out to be an elegant deal design.

For the underlying principles of creative deal design in negotiation with a multitude of practical examples, see chapters 4-7 of David Lax and James K. Sebenius, 3D Negotiation: Powerful Tools to Change the Game in Your Most Important Deals, Boston: Harvard Business Press, 2006.