As a fun and potentially valuable diversion from today’s grim headlines, I have a puzzler: you’ve printed up 3 million brochures with copyrighted photos for which you didn’t get permission. If you don’t use the photos, you’ll lose the election; if you do, you could be out $3 million that you don’t have. Advice for negotiating with the greedy copyright holder? But first, some useful background and context: an imposing statue of Theodore Roosevelt—high on his horse, flanked by an African man on his left and a Native American man on his right, both on foot—has stood at the entrance to New York City’s Museum of Natural History since 1940. While recent plans to remove it became something of a lightning rod among both progressives and conservatives, this controversy reminded me of a less familiar legacy of the 26th U.S. President: as a negotiator.

Roosevelt (“TR”) has traditionally evoked varied images: the sickly child who became a serious boxer and wrestler at Harvard, leader of the “Rough Riders” in the battle of San Juan Hill during the Spanish American War, trust-buster and national parks advocate as president, and so on. Yet TR had real chops as a negotiator: he sorted out a major coal strike and even brokered an agreement to end the bloody Russo-Japanese War for which he won the 1906 Nobel Peace Prize. He also understood the power of commitment in hardball negotiations.

When TR sought to demonstrate American sea power by sailing the navy’s new 16-battleship fleet around the world, he deadlocked with the Congress, which only provided him with half the needed funds. So, he gambled: if he sent the fleet halfway around the world and ran out of money, Congress would relent and provide the rest . . . which it did. Done deal, but no prizes for a “come, let us reason together” approach.

Now, the memorable, three-minute negotiation challenge from TR’s hard-fought election campaign of 1912. After reading the brief, embellished description of the situation—about which David Lax and I wrote some time ago*—pause to figure out how you would negotiate it. Then I’ll tell you what happened and tease out some lessons for today’s negotiators.

The Challenge

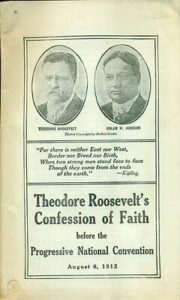

After his two-term presidency ended in 1908, TR grew disenchanted with his hand-picked successor (William Taft) and decided to run again in 1912 as head of his new “Bull Moose” party. Critical to TR’s campaign was a final whistle-stop railroad trip through key states. At each stop, Roosevelt’s stump speech would inspire the audience, who would be left with copies of a pamphlet, some three million of which had been printed and packed away in boxcars. On the cover was a “presidential” photograph of Roosevelt; inside was an inspirational speech, “Confession of Faith.” With luck, this strategy would clinch TR’s third term.

The train was scheduled to leave in a few days when campaign workers discovered a small line of print associated with each photograph that read, “Moffett Studios, Chicago.” Since Moffett held the copyright, each unauthorized use could cost the campaign one dollar. The potential $3 million cost of using all the pamphlets would greatly exceed the campaign’s available resources. The campaign workers panicked. They’d clearly screwed up but what to do now? Not distributing the pamphlets would likely cost TR the election. But if the campaign used the pamphlets without Moffett’s permission, they could be successfully sued for a ruinous amount.

The train was scheduled to leave in a few days when campaign workers discovered a small line of print associated with each photograph that read, “Moffett Studios, Chicago.” Since Moffett held the copyright, each unauthorized use could cost the campaign one dollar. The potential $3 million cost of using all the pamphlets would greatly exceed the campaign’s available resources. The campaign workers panicked. They’d clearly screwed up but what to do now? Not distributing the pamphlets would likely cost TR the election. But if the campaign used the pamphlets without Moffett’s permission, they could be successfully sued for a ruinous amount.

Quickly, the campaign workers agreed that they’d have to negotiate something with Moffett. They sent their Chicago operatives to learn about Moffett Studios and turned up more bad news. While Moffett had been a photographer for years, he had achieved little financial success. He was now approaching retirement, was reportedly bitter and cynical, and had a single-minded focus on money.

Imagine that the campaign staff turned to YOU for advice, what would YOU recommend?

The Strategy and Outcome

Insights and Lessons

Although creative and effective, the misleading tactics at the core of Perkins’s negotiating strategy do not represent a model process for crafting sustainable agreements that enhance working relationships. Returning to shortly to the ethics of Perkins’s tactic, I see at least four lessons from this episode.

First, as is very common in negotiation, the campaign workers focused almost exclusively on price. They missed the photographer’s potential interest in widespread publicity. Lesson: think beyond price to map the full set of interests potentially at stake.

Second, by focusing purely on price, TR’s staff envisioned only one kind of deal: the campaign paying somewhere between a little (success!) and up to $3 million (failure!). Had the staff started the negotiation by offering to pay Moffett something, their fears of an ugly price deal would have been self-fulfilling. That Moffett could end up paying something to the campaign—a logical possibility that in reality became the actual result—did not occur to them. While Moffett certainly would have preferred a big payday, the value of the publicity he got from the deal far exceeded the $250 he paid the campaign. Actually, this was a win for both sides, certainly relative to the pamphlets going unused. Lesson: beware bad assumptions. Check and recheck your assumptions; turn to trusted friends or advisers who are not too close to the situation.

Third, the campaign workers’ inability to see what Perkins immediately understood resulted from their focus on the negative aspects of their own problem. Having already blundered by printing so many unauthorized copies, the risk of disastrous political and financial consequences paralyzed their thinking. Had they paused to ask how Moffett saw the situation, they could have realized that Moffett didn’t even know he had an great opportunity with strong potential leverage. Ironically, Perkins’s framing of Moffett’s choice—coupled with a tight deadline—exploited Moffett’s tendency toward the same cognitive myopia displayed by the campaign workers. Certainly Perkin’s tactic did not guarantee success, but it seemed to be the best shot. Further irony: had Moffett carefully investigated the campaign’s situation, he might well have cleaned up financially. Lesson: don’t become a prisoner of your own problem; put yourself in their shoes and probe their situation as they most likely see it. (Even more ironically, while “put yourself in their shoes” is often a call to empathy, it can also reveal self-interested options.)

Fourth, while Perkins’s tactic was both creative and effective, it should leave us ethically uneasy about deceptive and manipulative tactics. Perkins’s deal plainly depended on Moffett’s unawareness of a highly material fact, giving the (unstated) impression that the campaign had a good walkaway option. Wanting no future relationship with Moffett and later proud of his cleverness, Perkins took quick action.  (Had Perkins felt differently, there were other options like offering Moffett the job of White House photographer if TR won or asking at the outset of negotiations what Moffett usually charged.) But before one sides too strongly with poor Moffett, outfoxed by a sophisticated financier, remember that it was a simple oversight that the campaign did not seek Moffett’s original permission to use the photos. If Moffett’s price was too high, the campaign would have just found another photograph. Did this oversight “entitle” Moffett to a windfall? If not, did that justify Perkins’s tactics? Wherever you come out on this, here’s a final lesson: while reaching ethical judgments can be tricky, ethics matter to negotiators.

(Had Perkins felt differently, there were other options like offering Moffett the job of White House photographer if TR won or asking at the outset of negotiations what Moffett usually charged.) But before one sides too strongly with poor Moffett, outfoxed by a sophisticated financier, remember that it was a simple oversight that the campaign did not seek Moffett’s original permission to use the photos. If Moffett’s price was too high, the campaign would have just found another photograph. Did this oversight “entitle” Moffett to a windfall? If not, did that justify Perkins’s tactics? Wherever you come out on this, here’s a final lesson: while reaching ethical judgments can be tricky, ethics matter to negotiators.